What's Real and What's Made Up?

I wrote the story Driven By Conscience using real locations and historical events, interweaving fictional characters and plot because I thought it would be a good way to immerse myself into another world. The story, which takes place between 1942 and 1945, has settings in Arkansas, Bavaria, Berlin, France, Manila, North Africa, and New York City.

Before starting to write, I dug into old records, letters and newspapers. Interlibrary loan got a workout. I talked to my mother, cousins and friends, and mined my memories of the World War II generation people in my life. I contacted history book authors and talked with museum curators and retired railroad men. I am grateful to those who shared their knowledge and experiences with me. The resulting bibliography provided the groundwork for the book. Creating the authentic feel of central Arkansas of the 1940's was as an important a part of the story as was the plot.

Heisenberg

As a biology student at Washington University in St. Louis, I studied Werner Heisenberg's scientific work. Years later I became interested in what happened to Heisenberg, a Nobel Laureate in Physics, during World War II, because he would have been in the prime of his career at that time. Heisenberg's essays and his wife Elisabeth's memoir became the springboard for the plot of Driven By Conscience.

Whether Heisenberg could have built an atomic bomb for the Axis powers has been the subject of conjecture since World War II. Driven by Conscience explores the role of Heisenberg and the German atom bomb, or as he called it, the uranium bomb. The story begins in 1942 with Uwe Johannes, Heisenberg's adventurous (and fictional) graduate student.

Werner Heisenberg was director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute during World War II. The German military scientific research effort began at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin, but the laboratories were relocated to a cave in the countryside as the war progressed. Before its relocation, area residents were angry at being bared from the institute during bombing raids, as exemplified in the novel's bakery scene. Elisabeth Heisenberg's description of the floral tributes to St. Florian was too good to exclude from the book.

The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute and the Heisenberg alpine country home are factual settings for Heisenberg and Uwe's fictional conversations. Heisenberg's dilemma was real. I drew upon personal experience of how scientists of Heisenberg's generation spoke and related to one another, and from reading his books and essays when writing the dialogue. The incident Heisenberg tells Uwe about Himmler's mother is true.

While Uwe's alteration of the World War I medal is a work of fiction, he could have worn the medal. Geneva Convention rules, to which the US and Germany were signatories, allowed captured soldiers to wear military decorations. The medal would have been a workable way to take material from Germany to the US, if it were possible to modify as cleverly as Uwe did.

North Africa

Klaus von Armin's German forces surrendered to the Allies in the outskirts of Tunis on May 12, 1943. Aaron Horton and Arnold Krammer's books describing German prisoners of war from capture to imprisonment in the US were helpful in recreating that process. Thanks to Dr. Krammer for suggesting an appropriate army rank for Uwe. The Third Reich's political allegiances with the Tunisian desert communities caused groups of soldiers such as Karl Becker and Walter Witte to escape in hopes of reaching freedom following von Arnim's surrender.

Thank you to Victoria Lambert, Heritage Assistant, Eastbourne Borough Council, Redoubt Fortress Royal Parade, East Sussex, UK, for sharing this photograph of von Arnim's command car.

Troop Transport

The prisoners' surprise at being provided with seats and nice food on transport was extracted from A German Prisoner of War in the South: The Memoir of Edwin Pelz, as was the distain exhibited by some soldiers who saw the accommodations as a sign of the Americans' weakness. Captured soldiers' letters home read like travelogues as they were transported to prisoner of war camps in America's interior. Like the soldiers traveling through the country in the novel, the prison train cars provided surprising views into American life. The number of cars parked in front of stores was so novel that some soldiers mistook the shopping areas for automobile manufacturing plants.

Jim Bowie

A young man Uwe's age would have been familiar with the American West through the popular books written by German novelist Karl May. I don't know whether Jim Bowie was featured in any of May's books, but such a character might have been lurking in Uwe's subconscious on his anxiety ridden train ride to prison camp. It was only fitting that a true figure from the American frontier with a history in Arkansas should greet Uwe when he crossed the state line.

POW Camps in the USA

Camp Robinson, located near North Little Rock, Arkansas, has been home to the Arkansas National Guard since 1917. During World War II, Camp Robinson became one of 700 prisoner of war camps operating throughout the United States. By 1945, Arkansas housed about 23,000 German and Italian prisoners. Four thousand German soldiers were at Camp Robinson. Ultimately the US held 425,000 prisoners of war.

Daily prison life in the novel is patterned from first hand accounts of imprisoned soldiers and International Red Cross inspection records. Prisoners worked in agricultural fields, played sports and put on amateur plays to pass time that extended into years. Soldiers attended classes in camp, earning college credit back home in Germany, so it wasn't a stretch to have Uwe teach his fellow soldiers basic physics. Grades were recorded in Germany even as the country capitulated to the Allies. After the war, credit for these classes applied towards college degrees.

Repatriated prisoners of war returned to their camps to visit after the war and were hosted by former guards. Inmates walked freely where they once had been prisoners. Many former prisoners of war made repatriation to the US after the war.

American camps followed the Geneva Conventions for treatment of prisoners of war. The War Department hoped fair treatment of German soldiers would be reflected in their treatment of American soldiers. American prisoners in Germany fared significantly worse than their counterparts in the states, but they were treated better than the Russians, who were not signatories to the Geneva Convention documents. After news broke of the concentration camp atrocities and the conditions of Allied POW's in German camps, food rations in the US POW camps were reduced in retaliation. Farmers who relied on prison labor for their crops supplemented the soldiers' diet because they were weak from hunger. Civilian co-workers, both black and white, brought extra lunches to enhance the meager rations of the POW's.

The scene in the novel when prisoners burned their uniforms following mandatory viewing of films showing Nazi concentration camp atrocities is recreated from a first hand account. Camp Holy Ghost trials and the penalty of hanging were real.

After the war, repatriated prisoners wrote back to the US, asking the farmers for whom they had picked cotton to please send food because their families were hungry.

Camp Robinson POW's built a to-scale mosaic map of their 9496 mile journey from North Africa to Camp Robinson. The importance of this distance to the real POW's inspired the novel's subtitle of 10,000 Miles One Way.

A German Prisoner of War in the South: The Memoir of Edwin Pelz provided invaluable insight into the POW experience in Arkansas. Pelz's explanation of how he felt about the war and Germany's defeat helped me understand what some of the soldiers were thinking. Pelz's description of the American citizens filling the prisoners' cups with ice water while their train waited at the station, and of his three am reception at camp by soldiers anxious for news, became part of Uwe's life experience.

I tried to imagine how a scientist such as Uwe would respond to the prison environment. I think Uwe would have taken each day as it came and would have tried to do useful things such as teaching fellow prisoners and repairing vehicles. After three years away from the laboratory, two of which were spent in prison, I think he would have been waiting for the war to conclude before deciding how to get on with life. When Colonel Edmund offered Uwe the chance to work on Project Stonehenge, he took the opportunity.

Project Stonehenge

Project Stonehenge is a fictional project, but the Manhattan Project was real. Because Arkansas housed nuclear missile silos post-WWII, I thought it would be interesting to inject a research laboratory there.

Characters

With the exception of the historical figures in the story, all of the characters are fictional. Bill Edmund is the embodiment of the good men of the World War II generation.

Nazi spies in the US during WWII

The characters of Imogene and Vivian were inspired by the real life story of Evelyn Clayton Lewis. Ms. Lewis, an Arkansan, was part of the infamous Duquesne Spy Ring operating out of New York City in the early 1940's. Ms. Lewis, along with 32 others, served prison time for her part in the operation.

Restaurants

Argenta Drug Company, Bruno's Little Italy, Mexico Chiquito and the White Pig Inn were in business in 1945 and still are today, except for The White Pig Inn, whose doors closed in 2019.

Anti-German sentiment in the USA during WWII

During World War II, my grandfather's neighbors started a rumor that he was German because he had blond hair and blue eyes. His heritage was mostly Scotch-Irish, but the US had plenty of German-American citizens. While in recent years much has been said about Japanese internment camps during WWII, less reported were the Italian and German internment camps (Undue Process: The Untold Story of America's German Alien Internees, Krammer, 1997). Due to the large number of American citizens of German ancestry, the situation in the US was somewhat different for German Americans than Japanese Americans. In 1945, seventeen percent of the US population had one or two parents of German descent, which is almost two out of every ten people. My mother-in-law attended mass in Fredericksburg, Texas during the late 1930's, where the American priest and congregation's first language was German. It was into this cultural mix that the soldiers in the story arrived.

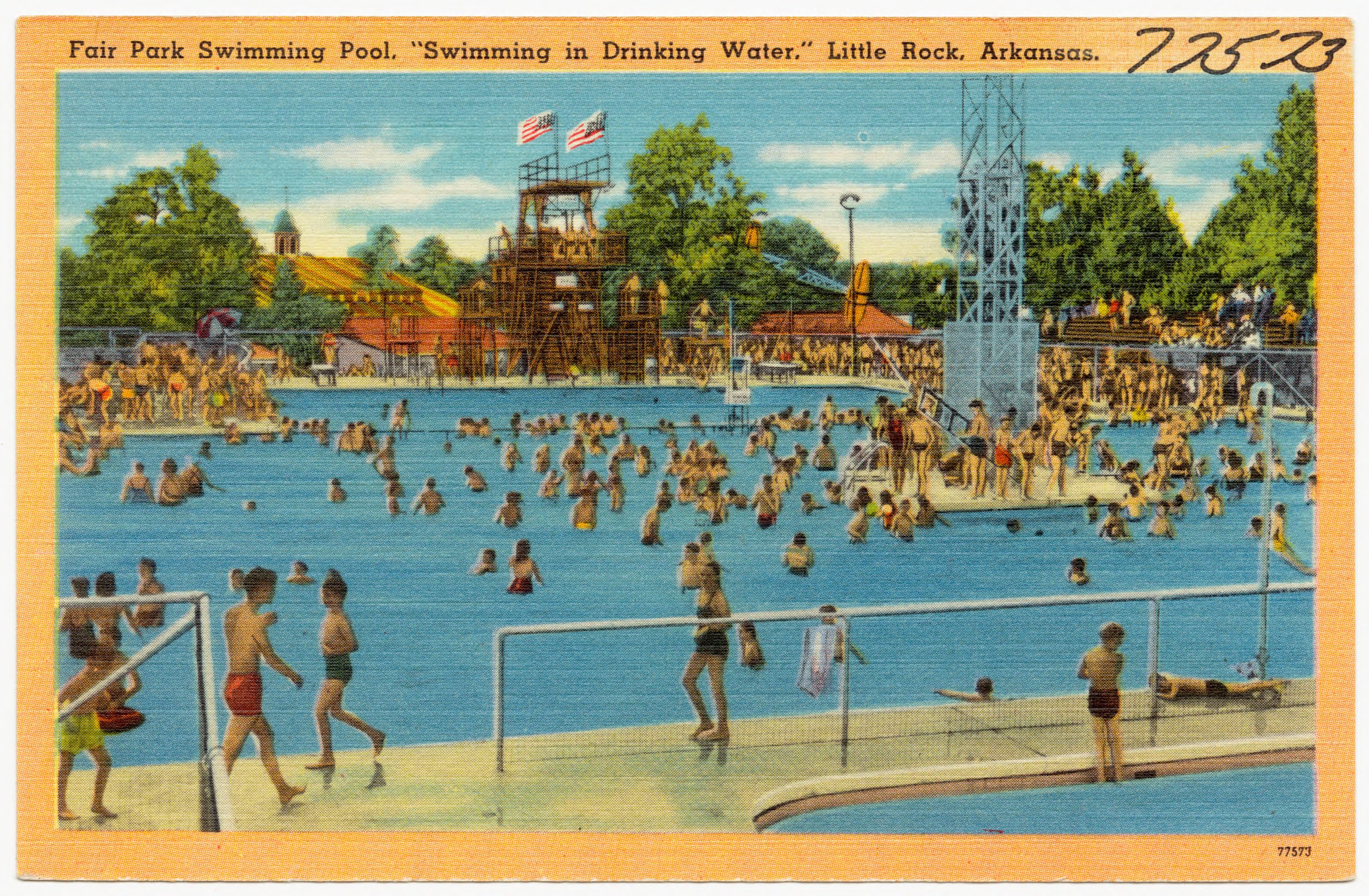

Fair Park Swimming Pool

Hot climates and swimming go together. Nowadays pools tend to be plain and built in cookie cutter fashion, as are playgrounds. Diving boards are gone due to liability concerns. That wasn't always the case, though, and I thought it would be fun to remember the days when communities, not just high-end hotels, built delightful municipal swimming pools.

Imogene and Dwight's quarter-boat scene shows how important it is that everyone should have water safety skills, and also that not everyone had the opportunity to learn them. Girls born in the first part of the 20th century often were left out of the fun. My mother, for example, learned to swim the same time I did, while her brothers and my dad had learned as children. In the postcard above most of the swimmers are boys. Opportunities for minorities to learn to swim were slim. The American Red Cross offered no cost swim lessons, registration open to all, at Little Rock's Fair Park Pool during the 1970's. Decades later, however, the statistics remain grim, with 70% of African American children in 2016 not knowing how to swim.

Little Rock Arsenal

General Douglas MacArthur was born at the Little Rock Arsenal on January 26, 1880. Today the Arsenal is a museum.

Fort Roots

Fort Roots is a veteran's hospital in North Little Rock, Arkansas. It has served veterans since 1921, and has been on the National Register of Historic Places since 1974. Less than ten miles from Camp Robinson, Fort Roots would have been a logical place for a wounded soldier to be transferred.

The Pine Bluff Arsenal began as a chemical weapons facility in 1941. It is still in operation today. The Arsenal arson plotline is fictitious, but the 'gypsy' camp area around it was real.

The 12th Man

As a graduate student at Texas A&M University, the 12th Man became my favorite Aggie tradition. If you've seen a Texas A&M University football game you’ve seen the 12th Man tradition in action. It dates back to 1922 when the Aggies were losing a game by a large margin because many players were unable to play due to injuries. Afraid he wouldn't have enough players to finish the game, Coach called for E. King Gill, a student in the stands, to suit up. Gill responded by running down and putting on the uniform of an injured player. He stood beside the bench for the entire game, ready to play. Energized by the show of support, the team turned the game around and won by 22-14, although Gill never left the sidelines. Today students show their support for the Aggie football team by standing during the entire game, ready to step forward like Gill did in 1922. The tradition is about loyalty and willingness to stand up and help.

When I wrote about young George Blackburn and his dog Porter, my mind kept returning to the 12th Man tradition. I wanted the second half of the book to be the part when all sorts of different people step up and work together for good.

Victory Girls

Victory Girls were real. Juanita's age is muddled in the novel because the actual Victory Girls were as young as thirteen, and that's just too young, even in a novel. The Victory Girls, whose activities were decried by the local citizens, were not American counterparts to the Japanese Comfort Girls.

Der Ruf

Der Ruf was a real newspaper published by German prisoners of war in the US. Thanks to Aaron Horton, author of a definitive study of Der Ruf and its contributors, for his encouragement and advice as I was beginning to write this story.

Quarter-boats

The quarter-boats were a novel housing solution for the new Arsenal workers. The Army Corps of Engineers moved them up river from Memphis to dock at Pine Bluff.

Arkansas Civil War History

Jake Holt's story of the soldiers from the 35th Arkansas Infantry Regiment is true.

Schools

Draughton's Business School, North Little Rock High School, Scipio Jones High School, and Philander Smith College were North Little Rock-Little Rock area schools. Founded in 1877, Philander Smith College is the result of the first attempt west of the Mississippi River to make education available to freedmen (former African American slaves). Former Surgeon General Joycelyn Elders is a famous alumnus.

Dialects

Despite the homogenizing effect of local speech patterns by the mass media, colloquialisms remain. Even today words like 'yonder' are still in use in the South.

Female FBI Agents

Gwen Weintraub was pushing the envelope in 1945 when she worked for the FBI. It would be almost three decades later, in 1972, before the FBI selected female agents. Up until then women working at the FBI did so in clerical jobs.

White Russians

Boris Pash, leader of the Alsos Mission, whose objective was the search and capture of Werner Heisenberg, was the son of White Russians. That means his parents opposed the Bolsheviks after the Russian Revolution of 1917.

Chocolate Chip Cookies

They were real.

<< Bibliography